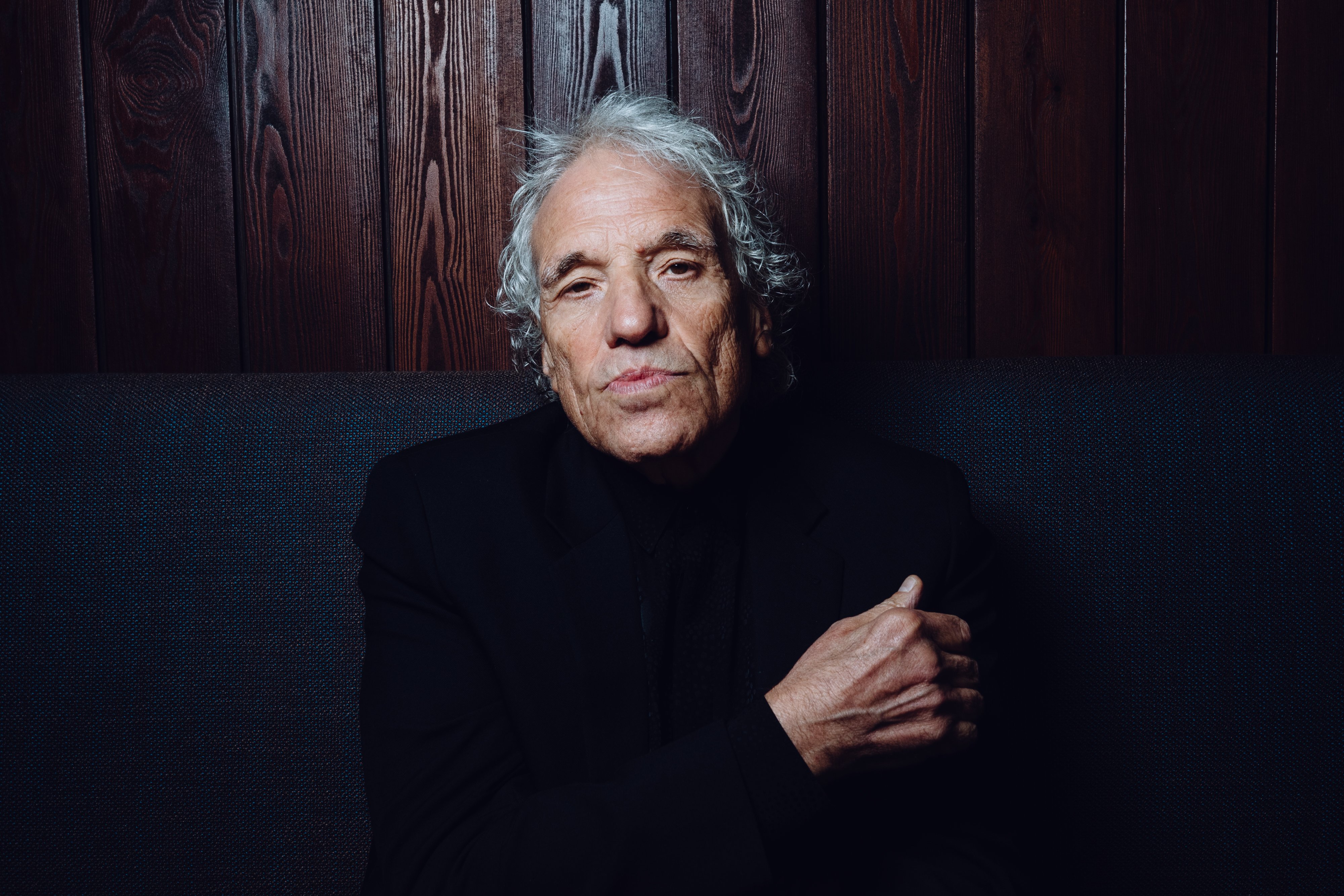

Abel Ferrara's Siberia, which premiered this year at Berlin Film Festival, is about to be released on Wink on November 12. This controversial and bizarre work is a continuation to the director's recent staggeringly personal films where he reflects on the eternal. Daria Postnova discussed with Ferrara working on Siberia, the difference between reality and fantasy, and (a tiny bit) the Safdie brothers.

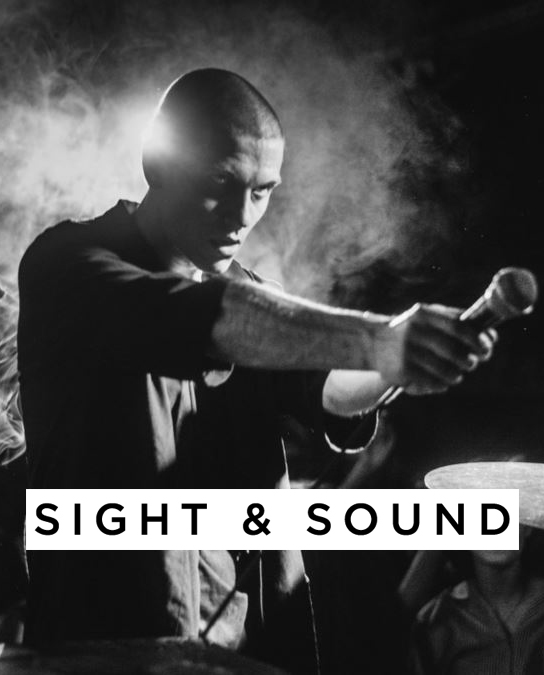

Photo / Michail Wilchuk / Russian World Vision

— I guess it would be interesting for many to find out why is your film called Siberia, considering that could've happened in any God-forgotten place on Earth.

— You know, when I started writing the set, I had no idea. These visions just came to me: bar in the middle of nowhere, two characters there — maybe one doesn’t exist — and they are played by the same actor. Why is it called Siberia? Cause it’s a sense of exile, a sense of magical mysterious place, exotic in a way. A place of irrelevancy. But again, this will all come from somebody from New York.

— The film's landscape is everchanging: a desert, then mountains, then green valleys... Had you been filming mainly in the studio or in different locations?

— We went to different locations, all those places are real. The "Siberian" scenes in we shot high up in the Italian Alps, it's very cold there. The desert scenes — in Mexico, closer to Arizona border.

— Is it important for us to see the difference between the real events happening to the character, and his fantasy? Does it matter?

I mean, what really is the difference? You sleep for 8 hours, a third of your life, you dream. During your wake-time… You know, sometimes you wake up and your dream feels more real than what you wake up to. So what really is the difference between your dream life and this? Or your memories, when you’re even awake? Your daydreams?

— So, there’s no differentiation for you between dreams and reality?

— No, not at all.

— We barely grasp the time period shown in the film. It could be several days, or several years in his head. Was there certain period of time you had in mind while filming?

— He was on a journey. He made it from the outpost to the mountains, was it a day, two days? In the desert he was walking. How far could he go? How long does it take to get from one place to another? It doesn’t matter. It’s a sense, it’s a spiritual journey, not a physical journey. But it is in a physical landscape.

— Maybe you could promote it as a road movie.

— Yeah, someone told me it is a road movie of the mind!

Russian World Vision

— I read that you’re practicing Buddhism and meditate. Did these practices shaped, in a way, your last films?

— Yeah, my practices are definitely changing me and my focus. They came to me when I stopped drinking and drugging. That was the big moment of change, and that practice helped me dealing with that, especially the meditation. It really helped me deal with everything.

— What did William [Dafoe] bring to the film that wasn’t in the script, and what perhaps surprised you?

— He brought everything. He brought himself, he brought his past, he brought his practice. His experiences. His abilities. His experience with me, his experience with other film people, his theatrical experience, life experience.

— Are you planning to shoot more films with him?

— I hope so!

One of the most interesting moments for me was Willem Dafoe's meeting with the last disciple who says to him: “Be human, fuck up, enjoy”. Is this the main idea, the slogan of the film in a way, considering that the main character is suffering from perfectionism, struggles to be human and tries to become a God?

Yeah, exactly. It's a quote from [Carl] Jung by the way. It was a beautiful one. I think we edited it a little bit, added the “shake your ass” part, so it cuts up to the Runaway dance part better [in one of the scenes Dafoe's character dances to Del Shannon's "Runaway"].

In your recent films, do you think you created some sort of autobiography in fiction? Do you really notice when you mix something personal with fictional stories?

In a sense, both autobiographical and fictional are personal. It’s all from yourself. I’m not hiding behind the character. In the last two films ("Tommaso"; "Siberia") we kinda just put the breaks on the characters and started to put the camera on ourselves. We’ve done it, and I’m sure we’re going to do it again if we live that long.

— You said in one of your interviews that “Bad Lieutenant” seemed separate from you although you helped writing and directed it...

“Bad Lieutenant” was another documentary on our life in a way, too. It was that blow by blow how to get high. If you go through my career, it's a whole gallery of sociopaths. And about "Tommaso" or "Siberia"... I don’t know how I’m gonna feel in 20 years. Ask me in 30 years when I’m hundred!

— There’s a feeling that your documentary works are developing right in parallel to your feature film career. Do you still have the same interest in making documentaries?

— Yeah, we’ve just shown one in Venice. It’s called “Sportin' Life”.

Russian World Vision

— And you came here right from Venice. How was it there? How did the film festival during the pandemic feel?

— It was night and day compared to Berlin. In Berlin no one had anything, and it was two weeks before the pandemic! “Siberia” was like the last crazy party. But “Sportin' Life” is about bringing “Siberia” to Berlin. So, considering you've been to the press conference, you might be in a movie! And then Venice was... Everyone with masks. It was courageous of them to do it. I hope nobody got sick. That was courageous for me to go there, sit in the theatre, and that’s courageous for me to come here because there are a lot fewer masks here.

— Unfortunately, you're right.

— Here no one believes in it, right? It feels like being in America. Everybody’s an expert on the disease. You know, they don’t need experts, they don’t need doctors. They don’t wanna wear masks. Everybody’s got their own philosophy, their own actual science.

Are there any younger filmmakers you find promising? For example, Safdie brothers — many people consider them to be devoted followers of your filmmaking traditions.

They are friends of mine, I know these guys from university, I’ve been in some of their movies. So, obviously, they gotta watch my movies growing up, they are from the younger generation. And I teach, so I see a lot of young filmmakers and I’m involved in a lot of their films.